I witnessed brutal repression and beatings in the streets of my city on multiple occasions. Before my eyes, security forces attacked people with batons, real bullets, pellet guns, and tear gas. I saw young women dragged along the pavement by their hair, treated in ways that even an occupying force would not inflict on the citizens of a conquered country. The only ones who came to help them were other young men and women nearby. Naturally, they too were beaten and later called rioters, rebels, or ‘corruptors on earth’, thrown into prison and sentenced to long prison sentences, or even to death.

So that you may understand what happens to our young people in prison, I will share a small part of my own experience there.

My intention is not to present myself as a hero, but to talk about what happens in prison, what I experienced there myself. Being sentenced to death had devastating psychological effects on both me and my family. One of the consequences was that my wife, who was pregnant at the time, lost our child as a result of the shock. We later separated. And that was just one of the minor consequences of a death sentence for those who are outside.

My intention is not to present myself as a hero, but to talk about what happens in prison, what I experienced there myself.

But inside the prison, it was a different world. During an interrogation, in an attempt to force a confession, they violently stuck a pen in my nose, causing me to lose consciousness. When I woke up, everything around me was covered in blood. On another occasion, they made me go down a staircase blindfolded. One of them kicked me violently in the back, causing me to fall.

Another time, around 5 o’clock in the morning, they called me by my name, told me to gather my belongings, and took me outside. It was snowing, and it was very cold. They made me get into a Peugeot 504 and drove me to a place with metal stairs. Inside a room, they suddenly threw a noose around my neck.

One of them said: “Repent, so you won’t go to hell.” I was so paralyzed with fear and stress that I was willing to do anything to end it quickly. My only wish at that moment was to be executed as soon as possible, to be free from this hell. For about fifteen minutes, they gradually tightened the noose. One of them said: “Tie it on the side so he doesn’t suffer too much, he’s a good guy.” Then, suddenly, a phone rang. Someone answered and said: “Stop. Hajji says to wait.” When they finally took me off the stool, my legs couldn’t hold me. I couldn’t even walk. Later, I learned that this was called a mock execution.

Later, I learned that this was called a mock execution.

These are just a few of the things I’ve been through. The same horrors are inflicted on our youth in prison — and on people in the streets — every day, in different ways. We can either look away and pass by all of this, in which case we don’t know what is left of their humanity, or do everything in their power to support their compatriots who are suffering.

I was one of those young people who could not remain indifferent to these atrocities.

The least I could do was to amplify the voices of the oppressed, which I did through my protest songs. Yes, that was my only crime — the reason they called me a rioter, a rebel, an enemy of God, and dragged me to prison. They beat me, broke my nose, and subjected me to a mock execution, all because I wanted the world to hear this suffering.

The least I could do was to amplify the voices of the oppressed, which I did through my protest songs.

After all, I was just a rapper. I doubt that any other singer or rapper has ever been sentenced to such a severe punishment. And perhaps for people in civilised societies, it is unimaginable that someone could be chained and imprisoned simply for their music, for songs that echo the pain of their people.

So read this short account and imagine the full story for yourselves.

Look at what they are doing to our workers, our teachers, our pensioners, our young men and women, our nurses, our students, and our professors. What crime have they committed, if not the crime of claiming their most fundamental rights? Are they the so-called rioters and enemies of the state? Or are they in the streets precisely to demand job security, legal rights, and a dignified life?

Over the last two years, they moved me from one prison to another. But no words can fully describe what I have seen. How can one describe the wait for the execution of one’s friends and loved ones?

I have repeatedly seen my fellow prisoners being taken to the gallows. In the secure wing of Ghezel Hesar prison, the cell door opened onto a corridor, which led to a small three-metre by three-metre courtyard, and then to another yard. It was in this second yard that the prisoners were taken to be executed. The sound of that door opening was the sound of death. We heard it time and time again.

I heard it when they took Qasem and Ayyub.

I heard it when they took Khosrow and Mohammad Qobadlou.

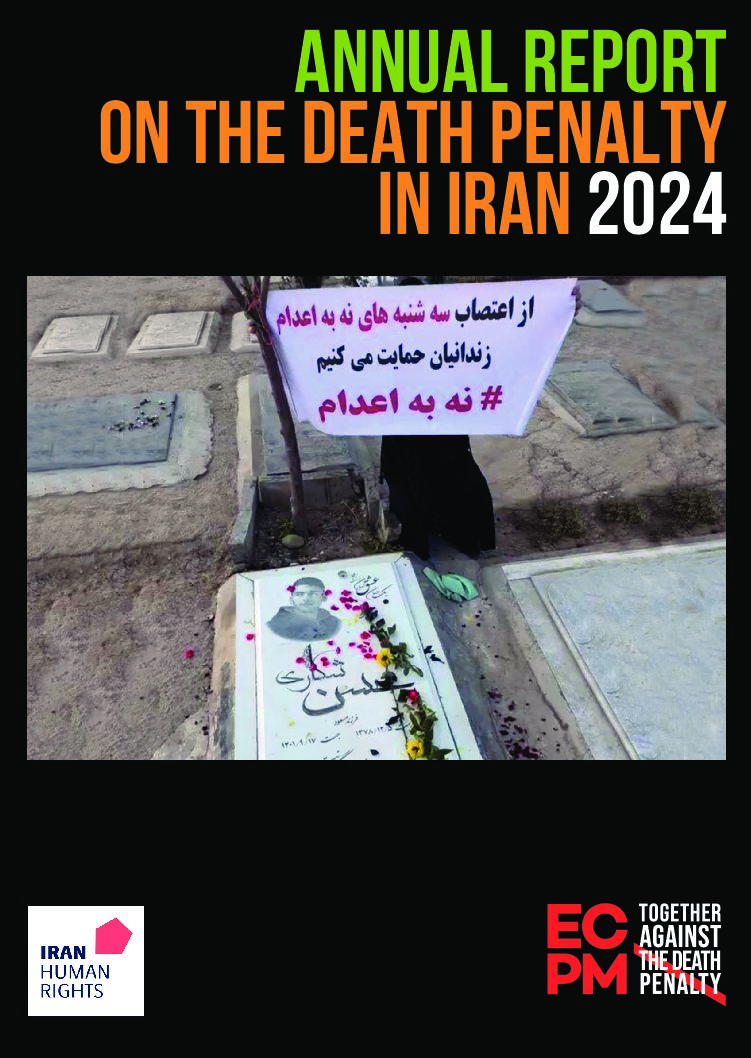

I heard it when they took Mohsen Shekari.

And we, those who remained, all heard it when they took so many of our friends and loved ones.