Since 2011, ECPM has been supporting local abolitionist networks including its partner, CTCPM, to propose a reform of the Tunisian penal system. Meetings between key actors in the struggle (NGOs, lawyers, doctors, journalists, etc.) are fostered through awareness raising workshops and political meetings.

Awareness raising activities target high school and secondary school students, as well as the general public, through an extensive educational programme (educational presentations, development of tools adapted to the political and cultural context), seminars and conferences held throughout the country and cultural events (exhibitions of works against the death penalty, film festivals, theatrical performances, etc.).

Exhibition of drawings on Avenue Bourguiba (Tunis, 2019)

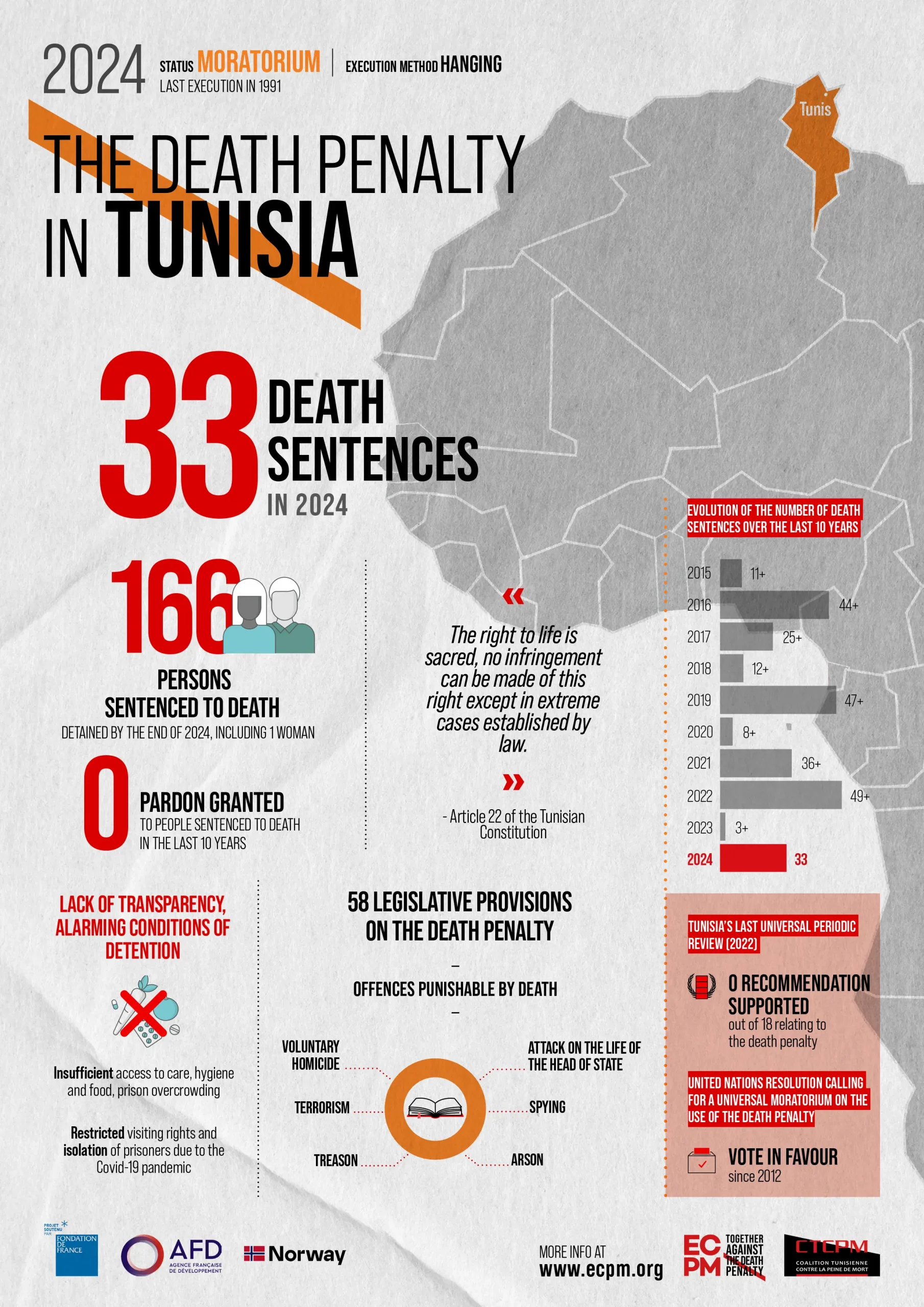

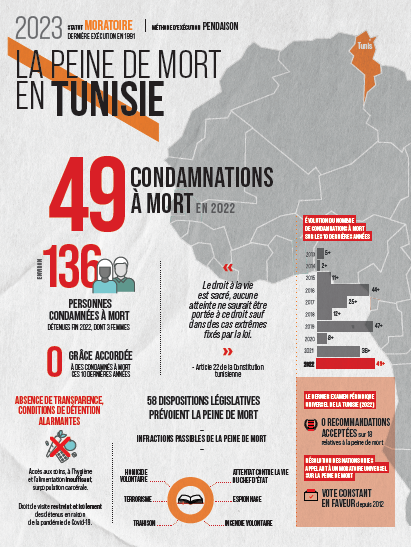

The situation of death row prisoners

As of 31 December 2022, 136 death row prisoners were detained in Tunisian prisons, including 3 women. The vast majority of death row prisoners were held in the Mornaguia prison; the women were held in the Manouba prison. In 2021, the occupancy rate of Tunisian prisons reached 126.4%.

Until 1996, those sentenced to death were isolated, held in solitary confinement, often shackled, even at night. In January 2011, in the wake of the popular protests that led to the fall of the dictatorial regime of Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali, the Revolution put an end to the most shocking abuses suffered by death row prisoners. They were once again allowed to have visits from their immediate families and to receive food baskets twice a week. Throughout their incarceration, until their sentences were commuted in 2012, death row prisoners lived in terror of being executed and developed pathologies linked to death row syndrome. Having suffered from isolation, prisoners experienced overcrowding, poor hygiene and food that was considered “vile”.

Paradoxically, the material conditions of detention of prisoners have deteriorated since the Revolution, as prisons are affected by budgetary restrictions and shortages. Although the situation varies enormously from one prison to another, depending on the centrality or remoteness of the region in which it is located, the medical and psychological care of prisoners on death row is generally inadequate. Death row inmates have not had access to educational, vocational and technical training programmes and have not been given the opportunity to work. There is no system for support or reintegration assistance for death row prisoners who have received pardons and have been released, so they are left to fend for themselves when they leave prison.