ECPM started working in Indonesia in 2008 in relation to the case of Serge Atlaoui, a French citizen sentenced to death. Since 2017, ECPM has been running an in-country project in partnership with KontraS aimed at galvanising advocacy with the national authorities in favour of abolition through the organisation of conferences, round tables and workshops. Training and awareness-raising activities on this issue are also organised, with a focus on young people and the media.

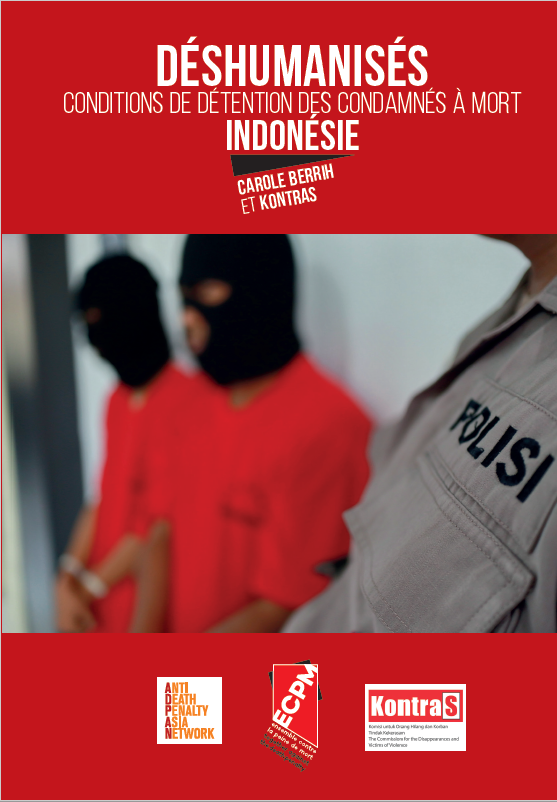

In 2018, ECPM launched its first fact-finding mission on death row in Indonesia. The mission report was published a year later. The delegation visited six prisons and interviewed a dozen people on death row, including foreigners and women. Interviews were also conducted with lawyers, prison administration staff and families of death row prisoners.

The situation of death row prisoners in Indonesia

In Indonesia, people can be sentenced to death for a wide range of crimes. Treason, aggravated murder, air crimes, drug trafficking, corruption, terrorism, child sexual abuse and international crimes. However, since independence, the death penalty has only been applied to four types of crimes: subversion, aggravated murder, terrorism and drug offences. NGOs estimate that more than 70% of all death sentences recorded since 2015 are for drug-related offences. Executions are by firing squad.

Over the last ten years, the number of death sentences has increased considerably, particularly since Indonesia’s “war on drugs”. In this context, the rights of prisoners are not guaranteed: the confidentiality of interviews with lawyers is not always respected and several people sentenced to death were beaten by the police until they confessed to their alleged crimes. According to death row prisoners interviewed during the fact-finding mission “Dehumanized”, their lawyers were not interested in their case and some of them were not in a position to defend them.

Conditions of detention amount to inhuman and cruel treatment. According to the law, those sentenced to death must be sent to Class I prisons. In these facilities, access to cultural, educational and sporting activities, or family visits are not allowed; prisoners are only authorised to walk for one hour a day in front of their cells, in handcuffs and shackles, and to engage in religious activities.

As a result of low budgets for food and health care, prisoners are dependent on their families for additional food or external resources, increasing the hardship faced by those with families living far from the prison or abroad. Many prisoners in Indonesia have been held on death row for decades, in daily fear of execution, which profoundly affects their mental health. Suicide attempts are considered reprehensible behaviour and punished by solitary confinement.