Exponential growth in the application of the death penalty in 2022

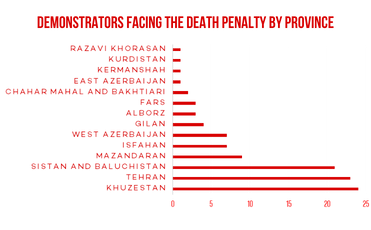

Since the beginning of 2023, 81 people have reportedly been executed, the majority for drug-related crimes. Among the thousands of people arrested, more than 107 protesters were reportedly charged and are at risk of being sentenced to death and executed. At least 500 people were executed in 2022.

For the first time since 2017, the annual number of executions in Iran exceeded the threshold of 500 executions in a year. The number of executions had already increased exponentially in the first half of 2022.

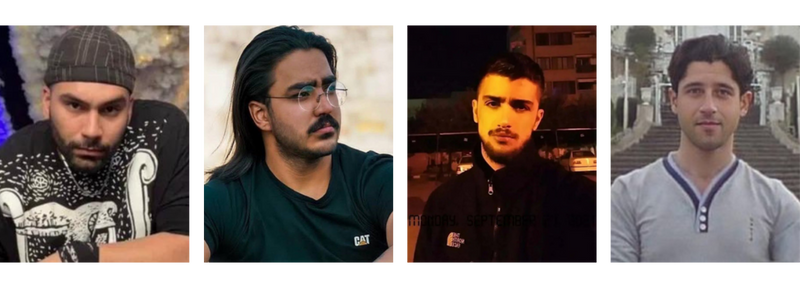

Executions directly linked to the demonstrations

Since the beginning of the protests, 4 people have been executed:

From left to right:

- Mohsen Shekari, 22 years old. Executed on 8 December 2022. Charge:

Moharebeh (enmity against God)

- Majidreza Rahanvard, 23 years old. Executed on 12 December 2022 in public. Charge: Moharebeh (enmity against God)

- Mohammad Mehdi Karami, 21 years old. Executed on 7 January 2023. Charge: Fisad-e-filarz (corruption on earth)

- Seyed Mohammad Hosseini, 39 years old. Executed on 7 January 2023. Charge: Fisad-e-filarz (corruption on earth)

It is difficult to obtain exact figures on the application of the death penalty in Iran. Although various NGOs have been able to compile statistics on the number of executions over the past few years, it is much more difficult to assess the number of people sentenced to death who are in prison. Furthermore, access to information on execution figures remains limited, as in the last five years about 34% of the number of executions have been officially announced by the authorities.

The international community estimates that 80 persons who were minors at the time of the events are currently detained and sentenced to death (figures provided by the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Islamic Republic of Iran).

Application of the death penalty as a tool of political repression in Iran

The application of the death penalty in Iran is not new. The Penal Code of 1925 provided for the death penalty for a number of offences.

However, after 1979, the number of offences punishable by death was expanded. Iran uses the death penalty as an instrument of political repression. Since 1978, Iran has experienced cycles of repression in which the application of the death penalty has always played a role. Since 2010,

7,052 people have reportedly been executed, including 187 women and 68 minors in breach of the law.

There are dozens of legal provisions governing the application of the death penalty in Iran, but most of the offences currently punishable by death have no precise definition and are therefore open to wide interpretation. The death penalty can be imposed for Moharebeh (enmity against God), Efsad-fil-arz (corruption on earth) and Baghy (armed rebellion). In addition, Article 220 of the Islamic Penal Code states that Article 167 of the Constitution may be invoked by the judge to impose Hudud penalties that are not explicitly mentioned in the legislation, based on Islamic law. The system of organisation of power in the Iranian Republic is very unique and places the Supreme Leader at the centre of all decisions. It is the Revolutionary Courts that are in charge of pronouncing death sentences.

These elements favour the political use of the death penalty, which is widely reported by the state media in order to instil fear. Every televised confession, trial or filmed execution is a reminder to Iranians that the authorities have every means at their disposal to suppress dissent of any kind. For the authorities, it is essential to show what they can do.

It is also with this aim in mind that public executions are organised and that entire generations have been marked by images that will never be erased.

In August 2013, a 13-year-old boy died by hanging while he was playing with his 8-year-old brother re-enacting a public execution. They had witnessed a large number of such executions since they were born.

It is also for this reason that in prisons such as Evin prison, when executions are carried out, political prisoners have been forced to watch and even participate, including by removing the bodies of the dead. The use of the death penalty has terrifying societal consequences. People do not get involved, express themselves, demonstrate in the same way when they risk being sentenced to death and executed. The death penalty is an instrument at the core of the Iranian regime’s system of terror.

Demonisation of the “ordinary people”

One feature characterising the application of the death penalty in Iran is the attempt to demonise “ordinary” people. This is done mainly in two ways:

- Firstly, in terms of the profile of those sentenced to death and executed for offences that have no clear definition; they are “ordinary” people, it could be anyone.

- Secondly, by imposing responsibility for the death penalty on the family of the murder victim. Since 2018, the majority of executions for murder have been carried out under Qisas: the families of the victims are offered a choice between granting a pardon or obtaining retribution in kind. Under the law of retaliation, families can choose to have the perpetrator of their loved one’s murder killed, in a state murder. The Iranian authorities consider Qisas to be the right of the plaintiff to decide whether or not the convicted person should be executed.

Discriminatory application of the death penalty

Individuals sentenced to death have diverse profiles: men, women, minors, artists. Most of them belong to minorities.

At least two minors have been arrested on charges carrying the death penalty. Mohammad Rakhshani-Azad, a 16-year-old Baluch boy, was arrested on charges of Moharebeh. His brother Ali Rakhshani-Azad, 15 years old, was also arrested and charged with Moharebeh. Mehdi Bahman, a writer and artist promoting interfaith understanding, was charged with espionage after giving an interview to an Israeli media. Mahsa Mohammadi, a 22-year-old microbiology student, was arrested for a tweet. She is accused of Sabol-nabi (insulting the prophet).

The Iranian people are determined, as shown by demonstrations in the streets, public statements and the positions expressed by young people on social networks. They have never received so much support from the international community. In this respect, the special session of the Human Rights Council held on 24 November 2022 was a historic moment.

Application of the death penalty in violation of the international law

From the start of the protests, it was feared that Iran would resort to the use of the death penalty against participants on a massive scale.

Death sentences and executions of protesters are not only contrary to human dignity and respect for the right to life, but also in breach of Iran’s international commitments.

“In countries which have not abolished the death penalty, sentence of death may be imposed only for the most serious crimes in accordance with the law in force at the time of the commission of the crime and not contrary to the provisions of the present Covenant.” The Human Rights Committee has taken the view that “the term ‘most serious crimes’ must be interpreted restrictively and appertain only to crimes of extreme gravity, involving intentional killing.”

Article 6, paragraph 2 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights ratified by Iran

Those who have been arrested in connection with the protests and executed, sentenced to death or at risk of being sentenced to death have faced charges including “inciting riots” for dancing or chanting slogans. These are not crimes that would fall into the category of the most serious crimes under international law.

Near systematic deprivation of the rights of the defence

Those arrested and detained are systematically deprived of their right to a defence, denied access to a lawyer, and are often subjected to torture and forced confessions. Of the 107 people facing the death penalty, almost all of them have been deprived of the opportunity to choose a lawyer.

Use of torture and forced confessions

Among the 107 individuals arrested or detained who are at risk of being sentenced to death, many have been tortured, often to force them to confess to crimes they did not commit.

- Mansour Dahmardeh, 22 years old, was subjected to 10 days of torture to confess to a crime that he did not commit.

- Abdolmalek Dousti was tortured, forced to confess to a crime he did not commit: the destruction and arson on a bank.

- Kambiz Kharout, 20 years old, was arrested, tortured and forced to confess to a crime he did not commit.

Some of their confessions were broadcast on TV, such as those of Mojahed Kourkour, who was forced to confess to the murder of a 10-year-old boy who had been killed by the security forces.

Unprecedented progress in the mobilisation of international mechanisms

On 24 November 2022, the Human Rights Council held a special session to vote on a Resolution presented by Germany.

This establishes the thirty-seventh fact-finding mechanism mandated by the Human Rights Council and is the first time that such a mechanism has so explicitly included the issue of the application of the death penalty. Of past resolutions, only that establishing the fact-finding mechanism on Libya included the issue of the death penalty. It is also the first time that a special session of the Human Rights Council establishing an international fact-finding mechanism has given such central consideration to the application of the death penalty.Almost all of the speakers, including the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, the UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Islamic Republic of Iran and representatives of Member States of the Human Rights Council who voted in favour of the Resolution, expressed concern about the death penalty.

“Deeply concerned about […] reports of charges that carry the death penalty being applied to protesters for offences that are less than the most serious crimes.”

Extract from the resolution adopted by the Human Rights Council on 24 November 2022

This unprecedented breakthrough is also a sign that the international community has finally reached a form of consensus on denouncing serious human rights violations by the Islamic Republic of Iran. It is to be hoped that such support from the international community will continue.

Perspectives

On 5 February 2023, Iran’s Supreme Leader issued an amnesty or reduction in prison sentences for “tens of thousands” of detainees. Implicitly, this was an acknowledgement of the scale of the repression of protests. This type of announcement is unlikely to be implemented and it is feared that, in parallel, death sentences and executions of protesters will increase.

“The term ‘organised and legalised killings’ is an apt description of the death penalty in Iran.”

Mohamed Rassoulof, released on bail on 13 February 2023 after spending several months in prison. Quote from the preface of the Annual Report on the Death Penalty in Iran 2021. Today, the director faces new charges and a possible further eight-year prison sentence.

The international fact-finding mechanism will begin its work. The UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Islamic Republic of Iran will present his annual report on 20 March 2023 at the Human Rights Council. This work and these reports should enable the international community to work towards ensuring that Iranian women and men, lawyers, human rights defenders, filmmakers, but also “ordinary people” are never again the victims of serious violations of their most fundamental rights, that the death penalty is never again the instrument of terror.

Since 2012, ECPM has been working with Iran Human Rights (IHR) to publish a joint annual report on the situation of the death penalty in Iran and to advocate for an end to executions in the country.